The fact that implementation of MGNREGA is mired in corruption is hardly contested. The ‘Scorpio’ or ‘Bolero’, which used to materialize almost magically after the election of Sarpanch, was largely attributed to the ill-gotten proceeds of MGNREGA, writes former IAS officer Sunil Kumar

The acronym MGNREGA is perhaps the most widely understood acronym of all government programmes in rural areas across the country. It has been in operation for nearly two decades now. It was widely hailed as the saviour scheme in tackling the fallout of national lockdown in March-May 2020[i] which witnessed reverse migration of over ten million people from the urban to rural areas. However, after nearly two decades of it’s functioning, the time is perhaps ripe to undertake a critical review of the scheme.

The Promise

MGNREGA promised to provide at least one hundred days of wage labour in a financial year on demand to any able-bodied person of a family in rural areas. In Para 1.28 of the Action Taken Report presented to the Standing Committee on Rural Development and Panchayati Raj in December 2024, the Department has stated that the average days of employment availed per household in the last five financial years has ranged between 47.83 days in 2022-23 to 52.09 days in 2023-24.[ii] Certain other studies show that only 4.1 percent of registered families got 100 days of employment under MGNREGA in 2020-21 across the country[iii]. The number of families benefited reached a high of about 8.6 crore in 2021- 22 and has now settled between 5 to 6 crores. The number of active job card holders under the scheme is around 12.89 crore.

Funding Pattern

The Funding pattern has been specified in Section 22 of The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005 (42 of 2005). Union Government has the responsibility of bearing the full cost of payment of wages for unskilled labour and upto 3/4th cost of material and wage costs of semi-skilled and skilled labour apart from partially meeting the administrative cost. The State Government has to meet the full cost of payment of unemployment allowance, upto 1/4th cost of material and wage costs of semi-skilled and skilled labour and the administrative cost of state council. This means that, on an average, GoI meets 90 percent and the State 10 percent of the total expenditure under MGNREGA. The 60:40 ratio of expenditure on labour and material is to be maintained at the district level.

The budget provided by union government reached a high of over Rs.1.09 lakh crore in 2021-22 and now ranges between Rs.80 to 85 thousand crore per annum. The States provide their share in line with the budget approved by the Department of Rural Development (DoRD), Government of India (GoI). Workers are expected to receive their payments within fifteen days but reports of delayed payments are received from almost all states without fail. Delay in payment for material component is much higher than for labour component.

Technology Dependent

To strengthen the implementation of MGNREGA, prevent frauds and ensure timely payment of wages, the rural development department has opted for high usage of digital technology. These include, inter alia, geo-tagging of all works undertaken under the scheme, use of GIS tools in planning, use of SECURE online application for preparing and approving work estimates and use of National Electronic Fund Management System (NeFMS) and DBT for payment of wages to almost 12.89 crore active workers. Adhaar seeding has been completed for all workers and payment has been mandatorily linked to Adhaar verification from 2025. However, the impact has been mixed.

Corruption in MGNREGA

The fact that implementation of MGNREGA is mired in corruption is hardly contested. The ‘Scorpio’ or ‘Bolero’, which used to materialize almost magically after the election of Sarpanch, was largely attributed to the ill-gotten proceeds of MGNREGA.

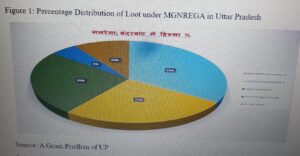

Most analysts agree that the degree of corruption varies from state to state and sometimes even within the district. According to a Gram Panchayat (GP) Pradhan in Uttar Pradesh, the situation is so bad in some parts of the State that less than 10% of the money is actually spent on work taken up under the scheme. The share of various functionaries starting from the Block Development Officer (BDO) and his office (which controls all administrative and financial powers), the unofficial contractor, the job-card holder and the rojgar sewak has been indicated in Figure 1 below.

Rojgar sahayaks call all the shots and they act as the agents of the BDO. The Pradhan of a GP is reduced to a helpless spectator if he refuses to be a part of the ‘organized loot’.

Theoretically, though the rojgar sahayak can be controlled by the GP by it exercising its power of annual ‘contract renewal’, enforcing the principle of ‘no work, no pay’ and removal by through a special majority. In practice, none of these work. The first two provisions have been bypassed by the Block Administration and the third provision is rendered ineffective as the rojgar sahayak ensures transfer of funds against the job-cards of more than half the ward members under the scheme without work and so they cannot be expected to support resolution seeking his removal. Consequently, the Pradhan can be reduced to a ‘non-entity’ in implementation of MGNREGA by the Rojgar Sahayak acting in collusion with the office of the BDO.

Poor Left in the Lurch

Various studies show that the scheme has benefited the southern and north-eastern States more than the poorer states of the east and north like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand and Odisha. It was only in the immediate aftermath of the covid pandemic that demand for MGNREGA was much higher in UP, Bihar, Jharkhand and Odisha than other States[iv]. The skewed implementation of the scheme leaves several questions unanswered and these require more research. However, there is unanimity among scholars that the poorest Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe households have benefited more from this scheme in all States despite all its failings in implementation.

What Ails MGNREGA

This question has exercised the minds of serious researchers. In an interesting essay[v] one author has raised the issue whether the problem with MGNREGA is structural or one of implementation. In his view the answer is complicated. He has referred to the structural and design issues and also how different States have devised ways to work around the system such as in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, who have opted for techno-bureaucratic solutions focused on problems of implementation. Even in Kerala, the scheme is being implemented by the Kudumbsree mission.

The then Minister of Rural Development, Shri Jairam Ramesh had reportedly observed in 2009 that the three goals of creating employment, durable assets and strengthening local self-government are hard to achieve at the same time and no state had managed to achieve all three.[vi]

Without getting into detailed analysis of the various aspects of implementation of MGNREGA, my contention is that the way the Act has been framed, the ‘right to work’ guaranteed by the Act is difficult to enforce by worker-citizens, who are from the weakest and the poorest segment of society. From the worker-citizens’ point of view, the Act would need to be recast as the design flaws are a serious impediment to realizing the objectives of the Act.

Worker-Citizen perspective

What are the entitlements assured by the transformative Act? These include, inter alia, getting at least 100 days of work on demand within 15 days (Section 3 (1)), payment of wages within 15 days (Section 3(3)) and payment of unemployment allowance in case of failure of the State to provide work (Section 7). The procedure for preparation of job-cards, their cancellation has been laid down in the first schedule of the Act.

As regards the implementation of the Act, details have been laid down in Chapter 4 (Section 10 to 19) of the said Act. Without going into the details, the key figures in the implementation of the employment guarantee schemes are the District Programme Coordinator – District CEO or Collector (section 14) and the Programme Officer – BDO (section 15). The role of the Gram Panchayat (GP) (section 16) and the provision relating to social audit by the Gram Sabha (section 17) seem to be more in the nature of an afterthought as the power to accord necessary sanction and administrative approval is vested in the District Programme Coordinator (sec.14(3)(c)). The Programme Officer (BDO) has been made responsible for sanctioning and ensuring payment of unemployment allowance to eligible households (sec.15 (5)(b)) as well as ensuring prompt and fair payment of wages to all labourers in the Block (sec.15 (5) (c)) apart from regular social audit by all Gram Sabhas (sec.15(5)(d)). These clearly indicate the subordinate role of both Gram Panchayat and the Gram Sabha.

Top-down approach

Despite the 73rd and 74th Constitution Amendment Acts (CAA) coming into effect in 1993, a perusal of the Act makes it amply clear that the two key players are the Union and the State Governments. Since this Act was confined to rural areas (section 1) urban local governments were automatically excluded. The role of the three-tier Local Governments – the GP, the Intermediate Panchayat and the District Panchayat – do not appear central to the scheme of things.

Since the MoRD had been running the rural employment schemes such as Rural Landless Employment Guarantee Programme (RLEGP), Jawahar Rojgar Yojana (JRY), Sampoorna Gramin Rojgar Yojana (SGRY), which were the precursor schemes to MGNREGS, the architects of the Act did not question the logic behind excluding local governments from the scheme schema and making the Ministry of Rural Development (and not Ministry of Panchayati Raj) the nodal Ministry for design and implementation of the Act.

The Department of Rural Development looked upon this Act as one of their regular schemes which had to be quickly implemented. In this they fell back upon the rural development department in the States and the Collector and the BDO in the district and the block. Distrust of the rural local governments is very much in evidence if read between the lines. Since Panchayati Raj was regarded as a legacy of the late Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, the role of the GP in planning and supervision and of the Gram Sabha in social audit, was carved out but that remained peripheral. The way the Social Audit Directorate of MGNREGA has functioned in most States testifies to the perfunctory role of Gram Sabha.

Excessive Centralization

That there is excessive centralization in MGNREGA is hardly in doubt. The fund flow and payments system represent over-centralisation. The Union government controls the purse strings. States are generally reimbursed by the Union government if they use their own funds to pay the workers. However, reimbursement can become tricky as anything ranging from non-submission of utilisation certificate on the prescribed format to not holding meetings of DISHA under the chairmanship of the Member of Parliament may be cause enough to delay (or withhold) release of funds by the Union Government.

The Union Government has also influenced disproportionately the kind of assets that need to be prioritised by the Gram Sabha. Works relating to different flagship schemes of GoI are routinely added to the list in the name of ensuring ‘convergence’ and better outcomes.

The DoRD is sitting on mounds of data. Fake pictures of workers, works under implementation with geo-tagging are being uploaded with impunity and payments being made in several states. There is no mechanism in place which can detect these anomalies in real time and stop payments. Reports of the CAG are few and far between. The Committee observed that in 2023-24, only 32% of gram panchayats had been audited. States and UTs such as Goa, Andaman and Nicobar and Puducherry are yet to establish a Social Audit Unit.[vii]

Toothless Legal Guarantee

The Act, Rules and the scheme guidelines have been so framed that no worker-citizen can ever successfully challenge the state government. Non-release of funds to West Bengal for over three years has left thousands of workers in the lurch as their wages have not been paid. Worker-citizens can neither sue the State government nor Government of India. Hence, the right to work, guaranteed under the Act, remains only on paper.

No Convictions

Section 25 of the Act provides for a fine of upto Rs.1000 on conviction to whoever contravenes the provisions of this Act. So far there is no reported case of even a single conviction by any court in any State under this Act. Like all other Acts, section 30 provides protection of action taken in good faith. It stipulates that no suit, prosecution or other legal proceedings shall lie against the District Programme Coordinator, Programme Officer or any other public servant within the meaning of section 21 of the Indian Penal Code (45 of 1860) in respect of anything which is in good faith done or intended to be done under this Act or the rules or Schemes made thereunder. This virtually rules out any conviction of any public servant for contravention of the provisions of the Act.

In fact the rules and guidelines are so devised that both State and Union Government can escape fixation of any responsibility. Delay or non-release of funds by the Union government can be attributed to non-compliance with the provisions of the scheme guidelines. Officials of State government can be let off the hook if they have brought the matter to the knowledge of superior authorities.

Unemployment Allowance

Payment of unemployment allowance is the sole responsibility of the State Government. Various reports of the Standing Committee of Parliament on Rural Development and Panchayati Raj consistently show that states, including Bihar, Karnataka and Rajasthan, have not provided unemployment allowances between 2018 and 2023[viii]. The Committee also observed that altogether unemployment allowance was admissible to 7124 workers between 2018-23 but only 258 workers (3 percent) actually received payment of unemployment allowance. The maximum number of workers entitled to receive unemployment allowance (2467) were identified in Karnataka but not one received the payment. The situation was no different in States like Bihar, Jharkhand or West Bengal.[ix] It may also be noted that only 25 States/UTs have notified the Unemployment Allowance Rules even after nearly two decades of the passage of the MGNREGA.[x]

According to the provisions of the Act, MGNREGA beneficiaries also receive compensation for delay in payment of wages beyond day 15. However, the Standing Committee noted that in 2022-23, despite compensation worth Rs 94 lakh being approved for 34 States/UTs, only Rs. 59 lakh was paid. In 2023-24, as of November 2023, out of Rs. 24 lakh approved, only Rs. 2.5 lakh was paid. This clearly indicates that provisions of the Act are routinely flouted and no officer can or has been held responsible for delay in payment of wages or unemployment allowance.

It may also be noted that the worker-citizen would be pitted against the might of the State were he/she to file a civil suit in court for enforcing the legal guarantees provided by the Act. S/he will need to bear the legal costs while the District Programme Coordinator or the Programme Officer would be defended by the State lawyer at public expense. This is a double whammy for the worker-citizen.

Successive reports of the Standing Committee of Parliament on Rural Development and Panchayati Raj have highlighted that the guarantees provided under the Act in respect of 100 days wage labour, timely payment of wages and payment of unemployment allowance have all been flouted with impunity in the last two decades. So far, no State has been able to provide 100 days of wage labour to all eligible households. Instances of delayed payments abound and even where compensation for delayed payment is approved, the same is not fully disbursed. The situation relating to payment of unemployment allowance is equally abysmal. To top it all, provisions of Sections 7, 8 and 9 of the Act are enough to absolve any Programme Officer or District Programme Coordinator or even the State of any responsibility regarding payment of unemployment allowance. And the Union Government could not care less.

Way Forward

If the right to work guaranteed by MGNREGA is looked at from the viewpoint of the worker-citizen, then the solution suggests itself.

Make Local Government Responsible for Enforcing the Guarantees

Based on the well-established subsidiarity principle, the responsibility for enforcing the guarantee would need to devolve upon the local government rather than the State government. It is the GP which is closest to the worker-citizen. Even the Block and the District are far too removed and it is well nigh impossible for a MGNREGA worker to meet the BDO or the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of District Panchayat or the District Collector. The Sarpanch/Pradhan is one functionary who is closest and most accessible to the worker-citizen.

What would this entail?

The responsibility for providing employment guarantee would fall on the GP. This would include providing at least one hundred days wage labour on demand to each household, timely and fair payment of wages and payment of unemployment allowance.

Share of Local Government in CSS

Accordingly, the whole architecture of scheme implementation would get turned on its head. Since the Union Government is providing this guarantee through an Act of Parliament, it is quite justified that it bear the lion’s share of the cost even though it is a State subject. However, the State and Local Governments would also need to bear their share in the true spirit of cooperative federalism. Hence, to begin with, Local Government becomes the third stakeholder. So the share of Union, State and Local Government should become 50:40:10 in MGNREGA.

Financial Strengthening of Local Governments

This would entail constitutional amendments providing for establishment of a Consolidated Fund of Local Government and granting Local Governments a share in the Goods and Services Tax (GST).[xi] A Budget Manual for Local Governments would also need to be prepared in consultation with the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) laying down in detail ,inter alia, the procedure for budget preparation and its passage by the Gram Sabha as well as procedure for booking receipts and expenditure from the Consolidated Fund of Local Government. A similar mechanism for Block and District Panchayat would need to be fleshed out.

Implementation Structure

Since the GP would be responsible for implementing MGNREGA, the GP Secretary would become the Programme Officer. He would then necessarily be a gazetted officer. Sufficient accounts, technical and engineering staff would need to be deployed in each GP for implementation of the scheme. They will work under the supervision and control of the GP. Role of the Block Panchayat and the BDO as well as District Panchayat and the CEO/District Collector would need to be reworked. Rural development, including implementation of centrally sponsored schemes, would necessarily devolve on the Local Governments and the present parallel arrangement of implementing them through the rural development department would need to be discarded. Rural development departments in the States have been singularly responsible for weak local governments even thirty-two years after the coming into force of the 73rd CAA. A department of Local Government working in close coordination with rural and urban local governments and a dedicated cadre of local and state government with provision for deputation from one cadre to the other and even to the Union government would become necessary and highly desirable.

Delimitation Commission for Local Government

Fresh delimitation of local governments to ensure that they remain administratively and financially viable units would be necessary. Towards this end, provision for delimitation of local government constituencies through an independent delimitation commission constituted on the pattern of delimitation commission for Lok Sabha nd Vidhan Sabha seats would need to be included in the Constitution.

Compensation for Delayed Payment & Unemployment Allowance

Existing provisions in the Act relating to payment of compensation for delayed payment and unemployment allowance in lieu of providing at work on demand tend to weaken the legal guarantee. It seems to presume that delay of more than 15 days in payment and providing work is more than likely. The very existence of such a provision reduces the imperative upon the state to provide work and posits two mutually contradictory obligations within the same bracket. These provisions tend to cover up the poor governance record and inefficiencies of the Government at all levels. As reports of the Standing Committee of Parliament show, these provisions are observed more in the breach and do not serve to enhance the welfare of worker- citizens. Both provisions are in the nature of corrective action which should be left to the Nyaya Panchayat to administer in case of the State/GP not fulfilling its obligation under the Act.

Enforcement Mechanism for Guarantees

The Nyaya Panchayats (the missing judicial arm of rural local government) would need to be constituted in all States/UTs. The Bihar model could be adopted by the States. The responsibility for adjudicating on cases relating to enforcement of guarantees under the MGNREGA must be entrusted to the Nyaya Panchayats. Worker-citizens should be able to haul the GP before Nyaya Panchayat for failure to implement their right to work. Failure of GP to honour the guarantees would entail fines. The maximum ceiling could be prescribed and it should be left to the Nyaya Panchayat to decide on the quantum of sentence. Failure to pay the fine within stipulated period ought to lead to imprisonment of the concerned functionary found guilty. If a GP functionary is held guilty by the Nyaya Panchayat, a provision to make it mandatory for the Sarpanch to move and seek a vote of confidence from the Gram Sabha within 15 days should be incorporated in the State Panchayat Raj Acts. This would ensure that there is also a political cost to be paid for administrative inefficiency.

Conclusion

The working of MGNREGA over the last two decades in almost all States makes it amply clear that the legal guarantee of providing at least hundred days of wage labour on demand per household in a financial year and ensure payment of timely and fair wages and unemployment allowance to worker-citizens remains largely unfulfilled. These are missing in action. If these guarantees are to become meaningful, local governments (especially the GP) would need to occupy centre-stage and a whole new administrative system would need to be ushered in. Government of India would need to shed its stranglehold over the scheme and give more autonomy to the local government and the state. The District Collector-BDO duo have obviously failed the test and are largely responsible for the failures of MGNREGA. The present arrangement needs a structural overhaul especially since demand for increasing the days of wage labour from 100 to 150 per HH in a financial year, adopting a more scientific and objective criteria for revising wages and even introducing this scheme in urban areas are being raised from various quarters. The scheme is important as it legally recognizes the right to work, assures the dignity of the poor and does not reduce them to just recepients of ‘doles’. The scheme has benefited the poor and marginalised but there is large scope for improvement. Only then can the triple objectives of employment creation, durable assets and strengthening local government can be achieved.

(Sunil Kumar is a visiting faculty in Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics and a member of Pune International Centre. He is also a former civil servant. Views expressed are personal.)

[i] MGNREGS Performance (2006–21): An Inter-State Analysis – Satyanarayana Turangi : South Asia Research Vol. 42(2): 208–232

[ii] Fourth Report of the Standing Committee on Rural Development and Panchayati Raj (2024-25), Para 1.28, pg.19 presented to Lok Sabha & Rajya Sabha on 17.12.2024

[iii] Ankur Bharadwaj & Ashwini Deshpande (2021). “MGNREGA: The Rescue Act in Need of Assistance” Centre for Economic Data and Analysis (CEDA), Ashoka University. Published on ceda.ashoka.edu.in

[iv] MGNREGS Performance (2006–21): An Inter-State Analysis – Satyanarayana Turangi : South Asia Research Vol. 42(2): 208–232

[v] What Ails MGNREGA?—It’s Complicated! – By Devashish Deshpande, Jan 26, 2017; https://www.huffpost.com/archive/in/entry/what-ails-mgnrega-its-complicated_in_5c0fe644e4b051c73eac0f49

[vi] The Continuing Relevance of MGNREGA – Sudha Narayanan, March 17, 2020; ttps://www.theindiaforum.in/article/continuing-relevance-mgnrega

[vii] Standing Committee Report Summary Rural Employment through MGNREGA – An insight into wage rates and other matters relating thereto; 27 February, 2024; https://prsindia.org/files/policy/policy_committee_reports/SCR_Summary_Rural_Development_MGNREGA.pdf

[viii] Ibid

[ix] Just 3% of MNREGA job seekers received unemployment allowance, shows central panel report; Raju Sajwan, February 13. 2024; https://www.downtoearth.org.in/governance/just-3-of-mnrega-job-seekers-received-unemployment-allowance-shows-central-panel-report-94429

[x] Fourth Report of the Standing Committee on Rural Development and Panchayati Raj (2024-25), pg.26 presented to Lok Sabha & Rajya Sabha on 17.12.2024

[xi] Towards Strengthening India’s Cooperative Federalism: Initiatives for Multi-Level Governance Reforms; Second Memorial Lecture; Dr. Vijay Kelkar; 1st December 2023; https://cess.ac.in/bpr-vithal-memorial-lectures/