Language can be freely learned, acquired and mastered by all. It is not a privilege or entitlement conferred by birth. It is this which makes it a unifier and an integral asset in the democratic nature of India. The nation, in the true spirit of our Constitution, must give space for all our languages without provoking any fear of the decline or extinction of any one language by being overrun by other languages, writes former IAS officer Juthika Patankar

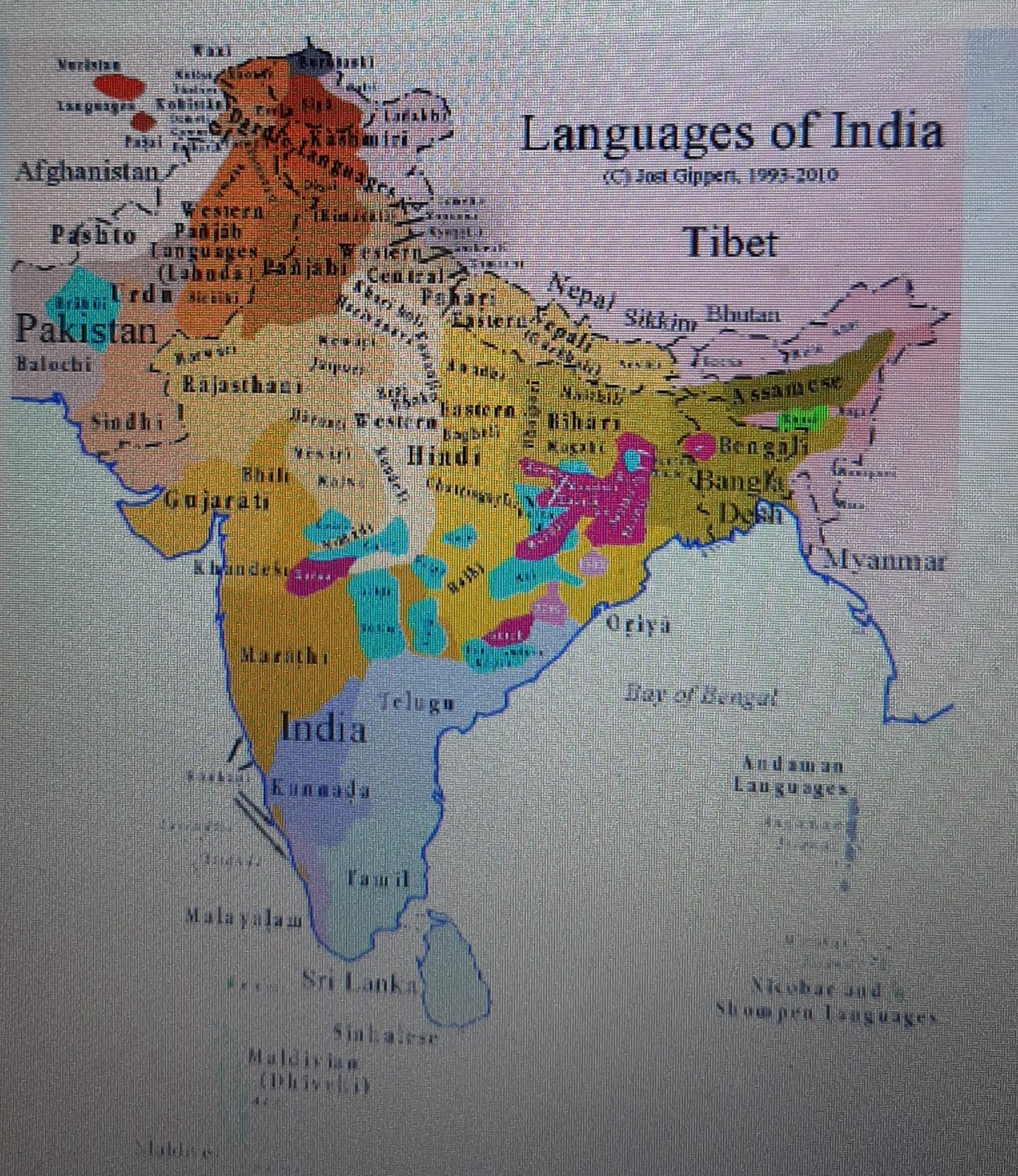

Language and mother tongue have always been sensitive and often prickly issues in India, a country which legitimately boasts of over twenty evolved languages and over 200 dialects. We are justly proud of this richness and diversity of our civilization. But language constitutes a huge portion of the identity of any person and is so much a part of ourselves that any threat of any kind, real or imagined, to the survival and possession of our own language can produce reactions ranging from extremely emotional to fanatical.

In India we have several contentious issues in languages. The Tamilian or Dravidian antipathy to Hindi and the fear of its imposition is well-known. There is always an ongoing debate about the benefit of imparting education in the child’s mother tongue. Local- level conflict over language is seen, for example, in the rivalry between Marathi and Kannada in Belgavi. The vociferous opposition to English and the passionate advocacy of regional languages is another permanent issue. And given that the federal units of India are divided on the basis of linguistic reorganisation is ample indication that language will always matter in politics.

I would like to state my view on how language can be converted from a divisive issue to a genuine unifier of this diverse country.

India, with its enormous and widespread regional imbalance in terms of economic opportunity, growth, law and order, material advancement and education or health facilities, sees large-scale migration from the backward states to better destination states like Punjab, Delhi, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. Maharashtra is the state with the highest in-migration while Uttar Pradesh has the highest number of emigrants. Given the distinct differences in languages and culture among Indian states, poor migrants would have a far higher degree of acceptability in destination states if they were taught the basics of spoken languages of those states. Language-learning should be an integral part of skill training so that not only is the passage made relatively easier, the bargaining power of migrant labour also gets augmented. Surprisingly, while emigration to foreign countries invites attention to the need to know the foreign language of the destination country at least at a rudimentary level, nobody seems to have emphasised the need to know the basics of the language of destination states within India.

Migrants are rarely welcomed genuinely in any region because for various reasons they are seen as the disruptive force in existing societies or communities. Here the social and psychological perception of ‘threatening outsiders’ far exceeds any rational acknowledgement of their undoubted contribution to economic growth. The single factor which estranges migrants from ‘locals’ is usually language, the inability of fresh migrants to speak or comprehend the local language. This at once arouses hostility, distrust, fear and suspicion at an overt or latent level. This is particularly unfortunate and a source of further hardship to those who are distress-migrants, that is, people who are forced to leave their homes to seek minimum or basic livelihoods. The trauma of leaving familiar locales and homes is further exacerbated in their case by the difficulties they face in access to jobs, housing, acceptance and belonging in their destination towns or cities.

However, since the ages, business communities and individuals who have gone to distant lands for commerce and trade, have acquired proficiency in the local languages of their chosen business destinations and have succeeded in assimilating themselves as an essential part of any local population. The case of Marwari and Sikh businessmen immediately comes to mind. These groups have migrated and settled in different parts of the country and have very successfully made themselves a part of local community. Such integration would not have been possible without their willingness prompted by business compulsions, to learn local languages. There is a lesson in this for migrant labour and particularly for policymakers.

Language and its development should never be dealt with on the basis of emotions. It is closely and inextricably aligned with economic opportunity. Economic development which pushes the boundaries of knowledge and research would invariably nurture evolution and expansion of any language which facilitates such progress. Languages cannot be protected or preserved or spread by fanatical pride or short-sighted policies based on populism. The shopkeepers of Udhagmandalam (Ooty) will continue to use Hindi for more custom among tourists regardless of state policy and migrants from UP and Bihar in Mumbai would inevitably have to replace their native versions of Hindi with the Mumbai version which is generously peppered with Marathi and Gujarathi.

Learning, or at least acknowledging the paramountcy of, any local language is equally important for migrants who move to other places for better career prospects, better income, greater professional variety or simply a better quality of life. Familiarity with a language other than one’s own is not only enriching in itself; it adds considerably to the educational qualifications and cultural attainments of any individual.

By suspending hostility, suspicion and fear of languages spoken in different regions and by adopting a conciliatory, if not embracing, acceptance of them would ease social tensions, minimise the need for irritating ‘political correctness’ and would add greatly to the joy of living.

There are important and vital lessons here for the misguided policymakers of language in India. First, Hindi spreads itself automatically and happily through films, music, entertainment, basic communication, trade and commerce. Second, by eliminating English out of foolish assumptions about colonial legacy, a huge part of India’s population is deprived of its constitutionally-guaranteed Fundamental Rights of freedom, equality, culture and education. Removing access to English denies citizens the opportunities for economic advancement besides being an infringement of their freedom to choose education and employment. Third, the regional languages of India carry significance and a huge cultural baggage of identity and accomplishment for their native speakers, which national policy cannot override or ignore. Fourth, the diversity of India is best preserved by allowing regional identities to thrive and flourish. Fifth, Hindi and English both serve India’s socio-economic interests and they do so by enjoying equal status as official languages, not at the expense of each other or by replacing regional languages.

A recent news item in the Indian Express mentioned that the number of persons in Mumbai, whose mother tongue is Marathi, has seen a further decline of more than 2% over the past few years. A vast and growing metropolis especially till the end of the twentieth century, Mumbai’s industrialisation and the economic opportunities it offered attracted migrants from all over India. Mumbai, or erstwhile Bombay, has naturally seen much conflict and anguish over Marathi. But Mumbai is a part of Maharashtra and it draws its identity, ethos and culture traditionally and for all times from the geographical region in which it is situated. And scores of migrants and settlers in Mumbai have become Marathi-speakers over their prolonged stay in the city. It would make eminent sense, therefore, if the status of Marathi in Mumbai is determined not by merely native Marathi-speakers but by counting all those who speak or read and write Marathi, in addition to their own tongues. This would not only reassure the native proponents of Marathi but would also underscore the ability of Marathi and Maharashtra to embrace with felicity all those who are not natives to the state.

Language can be freely learned, acquired and mastered by all. It is not a privilege or entitlement conferred by birth. It is this which makes it a unifier and an integral asset in the democratic nature of India. The nation, in the true spirit of our Constitution, must give space for all our languages without provoking any fear of the decline or extinction of any one language by being overrun by other languages.

(Ms. Juthika Patankar is a Visiting Faculty in Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, Pune and is a former civil servant. Views expressed are personal.)