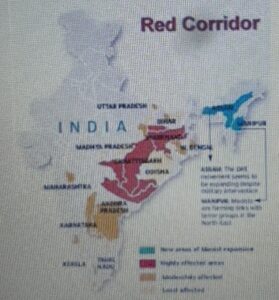

‘Sabka saath, sabka vishwas, sabka prayaas’ should involve not just the ‘triple engine sarkar’ but also winning the hearts and mind of all citizens and especially the weak and the downtrodden who seem to be witnessing ‘development’ pass them by. People led development plans, strengthening local governments and improving the low self-esteem of lakhs of elected representatives of local governments would go a long way in cementing the gains that have been made at a great cost in the so called ‘red-corridor’, writes former IAS officer Sunil Kumar

In the next two months the government expects the long-drawn Maoist insurgency, which at its peak in 2011 was spread over 223 districts, to end. The question, which appears to be weighing in the minds of the public, especially in the affected districts, centers around what next?

Media reports indicate that construction of road activity has picked up pace in the last few months and agencies are racing ahead to complete long delayed road projects in the worst affected districts by end of March this year. This includes all weather rural roads under the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY), state and national highways. Good network of road connectivity facilitates speedy movement and deployment of security forces and of citizens from their remote villages to hospitals, schools and the market. It also paves the way for speedy economic development of the area. Good and reliable transport system, electricity supply & distribution network and digital connectivity would considerably reduce physical distances and bring community, society and market closer. The pace of implementation of centrally sponsored and state schemes are also likely to gather pace.

It is widely acknowledged that the Schedule V areas dominated by the tribal population were the worst affected due to Maoist insurgency. These are also the areas which hold most of the country’s mineral and forest resources.

Issues of water, forest and land (jal, jungle and zameen) are very close to the hearts of the tribal people. To an extent, the way these concerns were handled in the past contributed to their alienation and breeding of anti-government sentiments. These need to be handled with care and sensitivity in the post-insurgency period. Effective implementation of the PESA Act and strengthening the Gram Sabha hold the key. However, this is easier said than done.

The contours of the governance structure were laid down by the 73rd and 74th Constitution Amendment Acts (CAA) and the Panchayat Extension to Scheduled Areas (PESA) Act, 1996. However, none of the ten Schedule V states took steps to notify the rules till as late as 2011. Six states notified the rules between 2011 to 2014. Thereafter, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh notified the rules in 2022 and Jharkhand is the latest state to do so in January 2026. Odisha is now the only state which has not notified the PESA rules even after nearly three decades. Pressure should be exerted on Odisha to notify the rules without any further delay.

However, the implementation of PESA Act presents an uneven picture across states. The rules notified leave considerable scope for ambiguity and conflicting interpretation in most states (barring Maharashtra to an extent). The major departments relating to water, forest and land have been loath to let go of their control which devolved to them during the colonial period. Powers granted to Gram Sabha in respect of these subjects under the PESA Act remain on paper in most states.

After seeing the working of the PESA Act, voices have begun to be raised by different tribal organizations in different states wherein they have demanded that certain ‘contradictory’, ‘incomplete’, ‘incompatible’ provisions incorporated in the rules need to be amended forthwith and brought in tune with the letter and spirit of the PESA Act, 1996.

By way of illustration, I will examine the suggestions presented to the government by the Adivasi Sarva Samaj of Chhattisgarh[i]. These inter alia point out how the definition of Gram Sabha in the Rules is not in tune with the PESA Act, making the Gram Panchayat Seceretary also the Secretary of the Gram Sabha is self defeating, all records of the Gram Sabha should be kept in the Gram Sabha office located in the village (as in neighbouring Madhya Pradesh), fix the minimum quorum of 50 percent of the Gram Sabha for deciding all issues and, more so, for issues relating to minor minerals, abolish the system of ‘secret voting’ in Gram Sabha (which goes against the traditional tribal traditions) and recognize the Gram Sabha as an independent legal personality that can own property, enter into contracts and sue or be sued in their corporate name just like the Gram Panchayat.

The proposed amendments include those pertaining to control over minor minerals. It has been suggested that the Gram Sabha should have the powers to mine or auction the minining rights of minor minerals; a share of the revenue earned from mining of minor minerals should be earmarked for the Gram Sabha and deposited in the Gram Sabha Fund and the Peace & Justice committee of the Gram Sabha should be authorized to stop illegal mining of minor minerals by imposing penalty on the offenders.

It has also been suggested that the existing provision, which makes it mandatory for the Gram Sabha to seek the advice of Forest department and restricts their power to fix the price and marketing arrangements to only nationalised forest produce, should be amended to grant the Gram Sabha full powers to fix the minimum support price (MSP) for all forest produce not below the MSP announced by the state government. It has also been suggested that the Forest department should be made to mandatorily seek the permission of the Gram Sabha (instead of just ‘informing’ the Gram Sabha) before implementing their projects within the boundaries of the Gram Sabha. Likewise, the Gram Sabha should be authorised to take cognizance of all non-cognizable offences under the Forest Act carrying penalty upto Rs.1000. The existing provision of just ‘informing’ the Peace & Justice Committee of the Gram Sabha regarding offences under the Forest Act should be amended and 24 hour timeline stipulated.

Regarding land issues, it has been proposed that approval of the Gram Sabha should be made mandatory in all cases of land acquisition and provision for appeal included in the notified rules must be withdrawn. Similarly it has been suggested that the rehabiltation of only ST families should be allowed in Schedule V areas and the local community should also be compensated for loss of community assets in any development project.

The government has also been requested to clarify the powers of the Gram Sabha in cases relating to violation of excise laws and what action can be taken by them against licensed excise vendors. Similarly, the police should be instructed to provide full details of all arrests to the Gram Sabha within 24 hours instead of existing provision of 15 days in the rules. Some other suggestions relate to control over village functionaries and operation of the Gram Sabha fund.

The memorandum submitted by the Sarva Adivasi Samaj is important for three reasons. First, it indicates the willingness of the community to go into details of legislations and rules framed thereunder and give suggestions which, so far, has been seen as ‘technical matters’ where the advice of the bureaucracy and legal experts only seem to matter. Two, it serves to bring to attention the anxieties of tribal groups which chiefly centre around the control of Gram Sabha over water, forest and land and the need to address their concerns over protection of their traditional ways of life including dispute resolution mechanisms. Three, it clearly signifies that there is a chasm between the functioning of different departments of the state government and the local community represented by the Gram Sabha.

In my view, effective implementation of the PESA Act, 1996 would go a long way in addressing these genuine concerns. There is urgent need to learn from the experience of better performing states like Maharashtra.

In order to ensure the tribal people reap the benefits of the peace dividend, the following steps could be taken.

One, protection of ‘jal, jungle aur zameen’, the three pillars around which life revolves in tribal areas, must be ensured over the short, medium and long term. This will go a long way in assuaging the feelings of the tribals. If there in unrestricted exploitation of minerals and felling of trees (as is widely feared), then that could again trigger the sense of alienation among them. Therefore, it is important that benefits of ‘development’ must flow to them in a manner which they can assimilate and in a language which they understand and identify with.

Two, at the heart of PESA Act, 1996 is the institution of Gram Sabha. It is important that the Gram Sabha in every village is truly empowered and has the final say on matters assigned to them – jal, jungle aur zameen. The provisions made in the PESA rules notified by the states after considerable delay need to be closely scrutinised. The state governments would do well to consult the tribal elected representatives, groups like Sarva Adivasi Sabha in Chhattisgarh, academics with deep understanding of tribal mores, traditions and psyche and civil society organizations which have been working in the area and bring about suitable changes sooner than later.

Three, the functionaries of all government departments, especially the Forest, Revenue & Excise departments, need to clearly understand the tribal sensitivities and be willing to cede their authority and control to Gram Sabha as per the provisions of the PESA Act passed by the parliament.

Four, the elected representatives of GP, Janpad Panchayat (Block Panchayat) and Zila Panchayat must begin to feel that they are ‘real’ elected representatives and not just those who carry out whatever orders they receive – whether from the Collector or their party leaders. This can be achieved if the state governments take care to spell out clearly the role & responsibility of ZP and Block Panchayat members.

Five, the work of elected representatives of local governments must be recognized as ‘full time’ work (and not part time) and their remuneration and perks fixed accordingly. Their time and effort must be valued as per objective economic indices and must be commensurate with their status as leaders of their community.

Six, the state governments would need to quickly iron out the conflicting positions taken by the local governments and the state departments. The role and responsibility of state departments would need to change into that of a ‘facilitator’ rather than a ‘competitor’ vis a vis the local governments. This would call for a relook at the hierarchical organization of departments and the contentious issue of placing them under the administrative control of local governments. The transfer of funds, functions and functionaries (so far elusive) to local governments as per the constitutional schema is urgently called for and the initiative has to be taken by the states.

Seven, giving a decisive say & control over District Mineral Foundation (DMF) Fund to the Gram Panchayat, Janpad Panchayat and Zilla Panchayat elected representatives (and redefining the role of District Collector in the operation of the DMF) will make available considerable ‘untied’ funds to them for undertaking works which the local community wants and not what is instructed from above.

Eight, the corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds of industries operating in the area must be distributed among the Gram Sabhas and only those works that are approved by the Gram Sabha could be undertaken by the industries as part of their CSR activities. This will help in addressing the existing trust deficit between the tribal communities and the industries.

Nine, since the Ministry of Panchayat Raj has already rolled out the Localisation of Sustainable Development Goals (LSDGs) and the Panchayat Advancement Index (PAI), it will be useful if CSOs and academic institutions are roped in to advise the rural local governments and explain to them as to where they stand on the PAI and what needs to be done to improve their position. Their advice and suggestions can be considered by the Gram Sabha and then based on their decision suitable development plans can be prepared and implemented. This could be replicated for the Block and the District as well.

Ten, suitable mechanisms to ensure accountability of elected representatives is absolutely necessary. The existing practice of placing the District Collector in the role of a judge over the conduct of ERs of local governments is not only undemocratic but also demeaning. These provisions need to be immediately deleted. The ‘right to recall’ provision exists in the Panchayati Raj Acts in several states. As suggested by the Second Administrative Reforms Commission, ombudsmen could be appointed in every district to consider all complaints against ERs and their recommendations could be placed before the Gram Sabha for final decision in case of ERs of GPs and likewise before the General Council of the Block and District Panchayats.

Eleven, adherence to rule of law by all state functionaries as well as citizens is the basic principle of our constitution. Without rule of law and accountability there can be no governance at any level. By ensuring that all violations of rule of law get punished (no matter by which person or authority), the trust deficit between the people and the civil administration can be bridged to a significant degree.

To my mind, the most important issue in Schedule V areas today relates to addressing the ‘democracy and trust deficit’. These cannot be removed through just holding of Panchayat elections or development of physical infrastructure alone. In order to make development inclusive and sustainable, it is imperative to give greater role to the people and trust their judgment rather than go for technocratic solutions alone. Cooperative federalism would mean involving the local governments as the third-tier of government in a big way and not just the union and the state governments. ‘Sabka saath, sabka vishwas, sabka prayaas’ should involve not just the ‘triple engine sarkar’ but also winning the hearts and mind of all citizens and especially the weak and the downtrodden who seem to be witnessing ‘development’ pass them by. People led development plans, strengthening local governments and improving the low self-esteem of lakhs of elected representatives of local governments would go a long way in cementing the gains that have been made at a great cost in the so called ‘red-corridor’.

(Sunil Kumar is a visiting Senior Fellow associated with Centre for Cooperative Federalism & Multilevel Governance in Pune International Centre and a former civil servant. Vies expressed above are personal.)

[i] District unit, Kanker of Sarva Adivasi Samaj submitted a 29 point memorandum dated 25.11.2025 requesting the state government to look into their suggestions for amendment in the PESA Rules notified by Chhatisgarh in 2022.