In view of three dominant sects- Shia, Sunni and Kurd- having their area of dominance in 18 provinces, no single party can form government alone. The voting pattern is also purely sectarian as each sect largely supports candidates of their own faction. During my visit to Iraq earlier this year I observed Iraqi society badly fractured on sectarian lines, which appeared to be result of departure of Saddam Hussein from power, writes M Hasan.

Even as main Shiite alliance in Iraq has emerged as majority bloc the internal battle for leadership has commenced between incumbent Prime Minister Mohammed Shia Al-Sudani and his staunch rival former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki. The Shia-led Coordination Framework (CF) alliance has announced that it had formed the majority bloc, which would ultimately nominate the next Prime Minister.

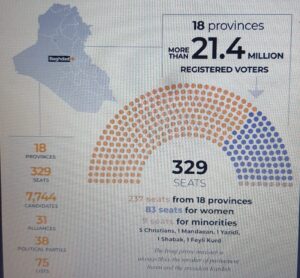

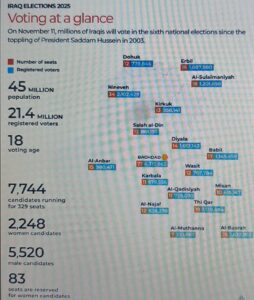

While Al-Sudani’s own group- the Reconstruction and Development coalition- has secured 46 seats in the 329-member Parliament, Malki’s party-The state of Law- has finished third with 29 seats. However, he has sought support from Sunni-dominated faction to regain power which he had lost in 2021. The move by Sudani, who is seeking a second term as Prime Minister, has given the Coordination Framework alliance of Shiite factions an outright majority of 175 seats in the Parliament.

(Left Shia cleric Muqtada Al Sadra (right: former PM Maliki)

But in extremely complex and highly fractured Iraqi political system in which Shia-Sunni and Kurdish forces are working at cross-purposes, simply getting enough seats is not guarantee to get the top post in the country. Since the US and Iran are deeply involved in the Iraqi political system, they directly influence the choice of leadership. During his first stint from 2022 Al Sudani has played a highly balancing game to keep these forces in good humor, however his tilt towards Iran has not gone down with the US. Iran-backed militia forces active in Iraq too have their role to play in the government formation.

After the fall of the regime of Saddam Hussein in 2003, the warring political forces had made an informal arrangement of power-sharing in the country. Thus, by convention (no constitutional necessity) in Iraq, a Shiite Muslim holds the post of Prime Minister, a Sunni is Parliament Speaker, and the largely ceremonial presidency goes to a Kurd.

Significantly Shia cleric Muqtada Al-Sadra, is out of the reckoning as his party had boycotted the Parliamentary elections held on November 11. He did not contest the election but his supporters are reported to have voted for Shia groups in his area of dominance in Baghdad, Karbala and Najaf. Al-Sadr is the most prominent spokesman of the rejectionist camp. He had emphatically declared his decision to boycott the elections and denounced the political establishment as corrupt and unreformable. He does not support power-sharing formula among Shia-Sunni and Kurd. He stands for all the power being given to a single largest party in Parliament.

Addressing the party conference in the northern city of Duhok, Sudani said his alliance “the Reconstruction and Development coalition is part of the Coordination Framework, which has decided to form the largest bloc.” He added that seeking a second term “is not about personal ambition, but about fulfilling his responsibility to see through the mission.” During his first term Sudani had pursued policies vowing reconstruction and stability in Iraq. He added that talks will begin among key parties about naming the new premier, speaker and president. Post-election talks between Shiite, Sunni and Kurdish parties in Iraq usually last for months, with constitutional deadlines frequently missed. But as Iraq has recently regained some stability after decades of war, key parties hope to reach a full package deal — premier, speaker and president — before the new parliament convenes in January. Last time the talks among three groups-Shia-Sunni and Kurd-lasted one year to finally accept Al Sudani as the Prime Minister.

Al Sudani’s party has now come first with 46 seats, followed by the Sunni Progress Party led by former Parliament Speaker Mohammed al-Halbousi, which won 36 seats. The State of Law coalition led by Nouri al-Maliki has secured 29 seats. The Taqaddum Party, which draws support from Iraq’s mainly Sunni west and north, won 27 seats and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) has secured 26 seats. There are also several smaller groups in all the states. Of the 329 seats 83 seats are reserved for women, five for Christians and three for other minority ethnic groups.

The Shia-led Coordination Framework said that it has formally designated itself as the largest parliamentary bloc, bringing together all its Shia constituent parties. Voter turnout in last week’s parliamentary elections was 56.11%, with 7,743 candidates competing for 329 seats. In view of three dominant sects- Shia, Sunni and Kurd- having their area of dominance in 18 provinces, no single party can form government alone. The voting pattern is also purely sectarian as each sect largely supports candidates of their own faction. During my visit to Iraq earlier this year I observed Iraqi society badly fractured on sectarian lines, which appeared to be result of departure of Saddam Hussein from power.

Sudani had been seeking a second term but many disillusioned young voters saw the election simply as a vehicle for established parties to divide Iraq’s oil wealth. In view of apathy of voters, specially in Shia segment over the prevailing unsatisfactory situation the clerics were deployed to issue edict (Fatwa) to exercise their franchise. The majority Shia community was also frightened over the political developments in neighboring Syria, Lebanon, Iran and genocide in Gaza. There were apprehensions that Shia community lose power in Iraq.

Within the CF, there are many disagreements shaping the discourse this election. Over the government’s policy towards Syria, allegiance to Iran, an aborted law regarding the Iran-aligned Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) that was strongly opposed by the United States, and, not least, the competing economic interests of the Shia factions. Three of the groups within the CF are also members of the PMF: the US-designated Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq (AAH) and Kataib Hizballah (KH), as well as the Badr Corps.

But the major rift is the political rivalry between Nouri al-Maliki and al-Sudani. Neither of them has made any secret of his ambition to lead a post-election government. While the campaigns had focused on the competition between the various Shia factions, al-Sudani and al-Maliki represented the two rival poles. But now victory has strengthened Al-Sudani’s position.

But al-Maliki and his “State of Law” coalition had harped on several themes to undermine al-Sudani’s tenure as prime minister. They have raised alarm about a surreptitious return of Baathists to power through the elections, and hundreds of candidates have been disqualified, rightly or wrongly, under the laws of de-Baathification. Opponents of al-Sudani have condemned the use of government resources in the campaign, indirectly accusing him of exploiting his office for electioneering. His detractors have also criticized the poor state of services after three years of the current government, al-Sudani’s relations with the new Sunni regime in Syria, and the warm relations between the prime minister and other Arab countries, which influential members of the CF view as hostile to Shia supremacy in Iraq. Even though second term to Al-Sudani appears to be assured, the alliance would continue to face internal and external fissures in next four years.

(M Hasan is former Chief of Bureau Hindustan Times, Lucknow)