The all-pervasive corruption in India is systemic, organized, and normalized, to say the least. It ranges from petty bribes in everyday interactions with government offices to massive scams involving politicians, bureaucrats, and corporate lobbies. According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index 2024, India ranks 93rd out of 180 countries, indicating that despite economic progress, governance remains compromised by unethical practices, writes former IAS officer V.S.Pandey

India is a democratic republic governed by the rule of law, where the Constitution is supreme and no one is above the law. The preamble and constitutional framework envisage equality, justice, and accountability as fundamental principles of governance. Yet, despite this robust legal edifice, corruption remains deeply entrenched in India’s administrative, political, and social fabric. The persistence of corruption in a country committed to legality and constitutional morality raises a serious question: How can corruption thrive in a nation governed by the rule of law?

This apparent contradiction calls for serious examination of both structural weaknesses and moral failures that has allowed corruption to coexist with the rule of law. The shocking aspect of the issue of all pervasive corruption is that whereas ordinary crimes committed anywhere are taken cognizance off but corruption, which itself is notified as a serious crime under our laws, goes unreported and unchecked, without any murmur.

The principle of the rule of law means that every individual, institution, and authority—including the government itself—is subject to and accountable under the law. It also implies that laws should be just, fairly enforced, and applied equally. However, the rule of law is not merely a legal construct—it also depends on the culture of compliance, institutional integrity, and moral consciousness of the people and their rulers. When these fail, the rule of law becomes rule by law—used selectively to protect the powerful and punish the weak.

The all-pervasive corruption in India is systemic, organized, and normalized, to say the least. It ranges from petty bribes in everyday interactions with government offices to massive scams involving politicians, bureaucrats, and corporate lobbies. According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index 2024, India ranks 93rd out of 180 countries, indicating that despite economic progress, governance remains compromised by unethical practices. From the “license-permit raj” of the pre-liberalization era to contemporary scams like coal block allocation, 2G spectrum, and bank loan frauds, massive scam of land allotment free of cost to the cronies, to name a few, corruption has evolved but not diminished. It manifests in bureaucratic delays, opaque decision-making, election financing, and manipulation of investigative agencies.

On paper we can say that our country has strong anti-corruption laws—the Prevention of Corruption Act, Lokpal and Lokayukta Act, Right to Information Act, and various vigilance bodies like the Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) and Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG). Yet, the implementation is abysmally dismal and the anti corruption bodies act in a manner which defies their very existence. Investigations are delayed, trials take years, and conviction rates remain low. The Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), which is supposed to be India’s premier anti-corruption agency, has often been criticized for being under the control of the political executive. The term “caged parrot” used by the Supreme Court captures the reality of compromised enforcement.

Undoubtedly, the root causes of large-scale corruption is the unregulated flow of money in politics. Political parties shamelessly justify their loot on the false ground that they need massive funds to contest elections, and this creates incentives to engage in corrupt practices—crony capitalism, quid pro quo contracts, and misuse of government machinery. Resultantly when the political class itself benefits from corruption, the rule of law becomes selective and ineffective. Transfers and postings of officers—especially in states—often serve as instruments of political patronage, turning bureaucrats into servants of political power rather than servants of the people. When administrative integrity collapses, the rule of law is replaced by the rule of influence.

Under our constitution, the judiciary is the ultimate guardian of the rule of law, yet India’s justice system is not only overburdened and slow but has become immune to the prevailing culture of corruption. With over 5 crore pending cases, justice delayed becomes justice denied. Powerful individuals exploit procedural loopholes and lengthy appeals to escape conviction. For instance, in several corruption cases, by the time judgment arrives, the accused have retired, died, evidence is lost, or public memory has faded. The absence of swift and certain punishment reduces deterrence and emboldens others to engage in corrupt acts.

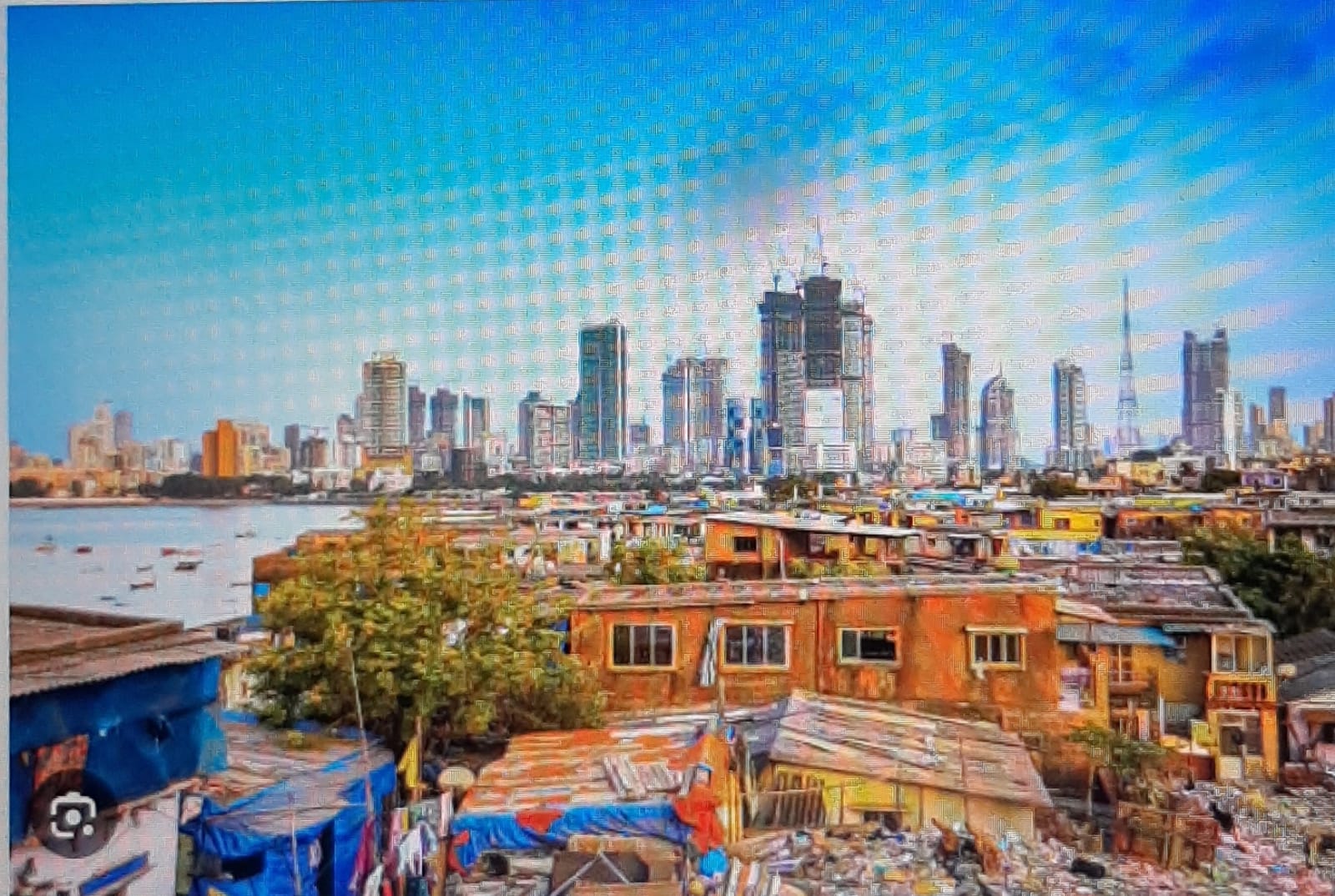

Situation has become so bad over decades that corruption has been normalized as a “necessary evil” or a shortcut to survival within a complex bureaucracy. Citizens are perforce made to pay bribes to save time, get certificates, or secure rights that should be freely available. This tacit acceptance has created a corruption culture, where moral indignation is replaced by resignation. When society tolerates corruption, the rule of law loses its moral authority. The result is that Citizens have lost faith in the fairness and neutrality of institutions when they see the rich and powerful escape accountability. All pervasive corruption diverts public resources, inflates project costs, and discourages honest businesses. The World Bank estimates that corruption costs developing countries like India billions each year. When elections are influenced by money power, democratic choice becomes hollow. The normalization of corruption weakens civic virtue and public morality, essential pillars of a democratic society.

India’s Constitution laid the foundation of a nation where law is supreme, not individuals. But for the rule of law to be meaningful, it must be lived in practice, not merely proclaimed in principle. Corruption has corroded the very soul of democracy by converting public offices into instruments of personal gain. As Mahatma Gandhi said, “The true measure of a society is how it treats its weakest members.” When corruption denies justice to the weak and rewards the powerful, it signals the failure of moral governance.

Restoring the rule of law in its true spirit requires political will, administrative integrity, and citizen vigilance. Laws alone cannot cleanse corruption; it is the collective awakening of conscience that can make India not only a country governed by law but also by justice and fairness. In his address to the Constituent Assembly on 26.11.1949 at the time of adoption of the Constitution, its President Dr. Rajendra Prasad had said-

“Whatever the Constitution may or may not provide, the welfare of the country will depend upon the way in which the country is administered. That will depend upon the men who administer it. If the people who are elected are capable and men of character and integrity, they would be able to make the best even of a defective Constitution. If they are lacking in these, the Constitution cannot help the country. After all, a Constitution, like a machine, is a lifeless thing. It acquires life because of the men who control it and operate it, and India needs today nothing more than a set of honest men who will have the interest of the country before them.”

(Vijay Shankar Pandey is former Secretary Government of India)