Corruption is not like an external growth or a carbuncle which can be clinically removed. It is a mindset, an attitude, a characteristic weakness of the human temperament which has to be reduced and eventually replaced by the strengthening of understanding, of perception, of integrity and of professionalism writes former IAS officer Juthika Patankar.

Have you ever wondered why we have never been able to tackle corruption in India? Even if, as Mrs Indira Gandhi famously averred, corruption is a global phenomenon, we in India seem to have had far more than our fair share. It isn’t as if successive governments haven’t tried to address the problem. From legislation like the Prevention of Corruption Act 1988, Prevention of Money Laundering Act 2002 to strident promises like ‘na khaunga na khane doonga’ India’s rulers have taken cognizance of corruption. The Bofors gun procurement corruption allegations brought down the government of Shri Rajiv Gandhi, the then Prime Minister. The dubious demonetisation move was also the apparent fulfilment of a promise to eliminate black money. But corruption reigns supreme. Bofors gave way to the Rafael deal allegations whose volume was far greater than Bofors; demonetisation proved futile in its avowed aims and big-time money launderers continued to flourish. Corruption has become an integral part of our mess and it is even euphemised by terms like ‘suvidha shulk’ (convenience fee).

But to revert to the question of why we have not been able to tackle corruption, the following arguments may provide some answers. At the outset, it is clarified that henceforth the corruption discussed in this article refers to the corruption among government officials and among all those who enjoy some degree of power, howsoever slight, which they can abuse to make money illegally. Corruption on a gigantic scale such as corruption in big companies, major financial players, political corruption for extraordinary electoral and power gains is beyond the scope of the present discussion.

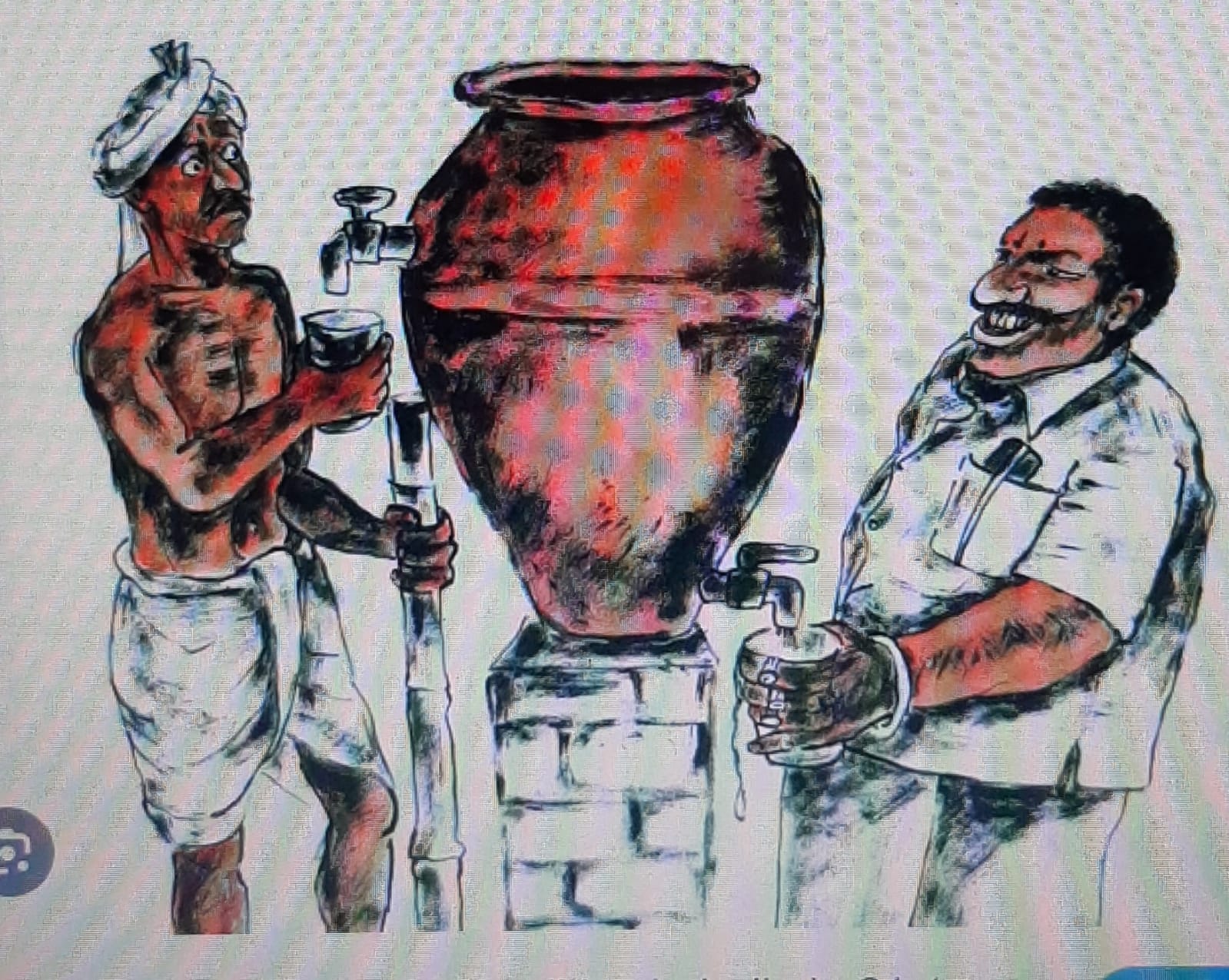

The requirement of bribery for the accomplishment of any task which involves Authority is a huge irritant, rather like the insistent assault of flies and mosquitoes. Why are we unable to do what we are mandated and duly paid to do, without illegal gratification? As far as the various levels of bureaucracy and all other government functionaries are concerned, the answer lies in the fundamental absence of professionalism coupled with monumental stupidity.

What, in turn, accounts for the fundamental lack of professionalism? In Government, except for some emphasis on the subject during the ‘nineties, there is no place or importance given to on-the-job training. Regular professional training for every level is an absolute imperative. It updates one’s knowledge, sharpens professional skills and provides the opportunity to exchange ideas and views across hierarchies in a power-neutral space which also induces a spirit of general cooperation and mutual understanding. But barring the topmost level of the civil service, training does not happen for any other group.

The reason that training is noticeably absent is that supervisors are neither willing nor able to spare their very limited number of subordinates to take a week or so off for training. Large numbers of posts in the government hierarchy remain vacant for years and there is no attempt to streamline duties, procure an adequate size of work-force or periodically upgrade the abilities of existing staff. Apathy and inefficiency, often born of, inter alia, natural stupidity, is the underlying reason for vacancies even when persons are desperately needed. Nobody has ever held our public service recruiting agencies to account for not doing their job.

At the top level, while there is no dearth of training opportunities and programmes, there is no attempt whatsoever to deploy the freshly-trained officers usefully or to encourage discussion and debate on training content so that it could prove to be really valuable in augmenting efficiency and information. And hardly anybody at the highest level feels the need to transmit the importance of training and provide the same for his/her subordinates.

A lack of professionalism on the job means that employees rarely retain a coherent or cogent idea of their precise duties. They expend no thought on improving their own efficiency, innovating procedures for greater speed and efficacy. They allow the monotony and the drudgery of their tasks to overpower them completely till they are left with no freshness of outlook or zeal or energy. This is then fertile ground for corruption. The job is seen only as a means of obstructing the client to extract money. The actual performance of the job brings no pride in the achievement. There is no feeling of gratifyingly raised self-esteem for having been instrumental in a duty efficiently discharged.

The relative absence of channels of free and informal communication all the way down the hierarchy means that employees and supervisors rarely meet in a cordial environment where the former can be told about the overall goal, structure or scheme of which the employee’s own role might form a small but not insignificant part. If every hierarchical level understands the value and indispensability of its own job, the employees at every level would feel intimately connected to the wider scheme of things. Their tasks would assume significance and they would like to claim credit for a job well done. They would feel they have a stake in the final success of the enterprise. This would replace the ennui, boredom, discouraging apathy they would otherwise have brought to their work. In turn self-esteem would rise and the chances of their avidly and avariciously seeking illegal payment would be considerably reduced. The corresponding response of appreciative acknowledgement by the client of their professionalism would further bolster self-esteem and a desire to ‘own’ their given job.

Work culture in India leaves much to be desired. A workplace which is salubrious and aesthetically pleasing can produce kindly feelings in an employee towards the job and consequently retain his/her self-respect. Professionalism matters in work culture insofar as it involves the welfare of employees too. Working hours and lunch breaks need to be precisely stipulated and strict adherence to these would instil discipline both for work and leisure. In our country while the general complaint is that government employees don’t work, nobody seems to have noticed that they don’t do much in their leisure time either. Work efficiency is wrongly perceived to be the maximum time spent in the office rather than real productivity within prescribed work-hours, a healthy body and cheerful spirit. Punctuality in arriving at work and equally punctuality in quitting work at the end of the day would mean much better time management. This would translate into more time for families. Engaging pursuit of individual interests, outings and consequently an expectation of better public spaces. The process would bring about improvement in various facets of life, including civic amenities. Employee welfare measures which can lead to a greater identification with and professionalism on the job are especially important for the police, security forces and other such professions which, by the very nature of their duties can instil negativity and even anti-social emotions in the staff.

Professionalism on the job implies that within your work-space or the delineated territory of your sphere of authority, you are the boss. The curious practice of deferentially yielding one’s chair to one’s supervisor during a visit or inspection at one’s workplace does not appear to suggest a professional outlook on part of either supervisor or employee. Owning your work territory, both spatially and metaphorically, means owning responsibility for the proper discharge of duties in that role. Again, this is important for instilling and preserving self-esteem.

Finally, a word about stupidity. Stupidity is intricately aligned with corrupt practice. Cheating and dishonesty provoke an equal but not opposite reaction. Corruption has a cascading effect and it multiplies quickly too. So, the net result is that everybody is constantly cheating everybody else. What then is the gain? Ultimately, the whole enterprise of corruption brings down all that the corrupt person desired to attain through greed and ill-gotten money. Corruption-free transactions, on the other hand, would continue to fatten the proverbial golden goose who would continue to supply the golden eggs. Not being able to grasp this is colossal stupidity.

Corruption is not like an external growth or a carbuncle which can be clinically removed. It is a mindset, an attitude, a characteristic weakness of the human temperament which has to be reduced and eventually replaced by the strengthening of understanding, of perception, of integrity and of professionalism. Reduction of the tendency to be corrupt can be brought about by a variety of measures which boost the worker’s self-esteem, his/her professional pride and skills, and his /her owning responsibility for the assigned job. It will not happen overnight but making a start will eventually produce an impact. This would need to be sustained through constant practice till the society reaches a stage when its natural inclination is to be honest rather than to cheat.

(Ms. Juthika Patankar is a visiting faculty in Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics and a member of Pune International Centre. She is also a former civil servant. Views expressed are personal.)