In India, we seem to have an instinctive aversion or distrust of these ‘conveniences’ meant for pedestrians. Subways are rarely clean, they are ill-lit and often unsafe. Anti-social elements, vagrants, drug addicts are persons who make subways their haunt and make them menacing for the average law-abiding citizen, writes former IAS officer Juthika Patankar

A recent news item mentions that the Honourable Supreme Court of India has stated that proper footpaths for pedestrians is their constitutional right. According to the news item, the Supreme Court has directed all the states and union territories frame guidelines to ensure proper footpaths for pedestrians. Reference has been made to ensure the facilitation of persons with disabilities and also to the removal of encroachments on the footpaths.

Naturally, it is heartening to see that the issue of pedestrians’ safe walking has been upheld by no less an authority than the highest court in the land, the Supreme Court of India. But with due respect to the orders of the Honourable Court, one is left wondering why the states and union territories need to be directed to frame guidelines for footpath creation and maintenance. Granted that apparently nothing happens by way of citizen-oriented governance until the judiciary takes cognisance of issues, surely the local governments in our towns can grasp the idea of making pavements as a basic need for walkers without guidelines from state and union governments?

It is the abject and abysmal failure of local governments which has been sharply highlighted by this news report about the Supreme Court and pedestrians. It should be glaringly obvious to any civic authority that the provision and upkeep of user-friendly footpaths is absolutely the first step in making our roads fit for walking.

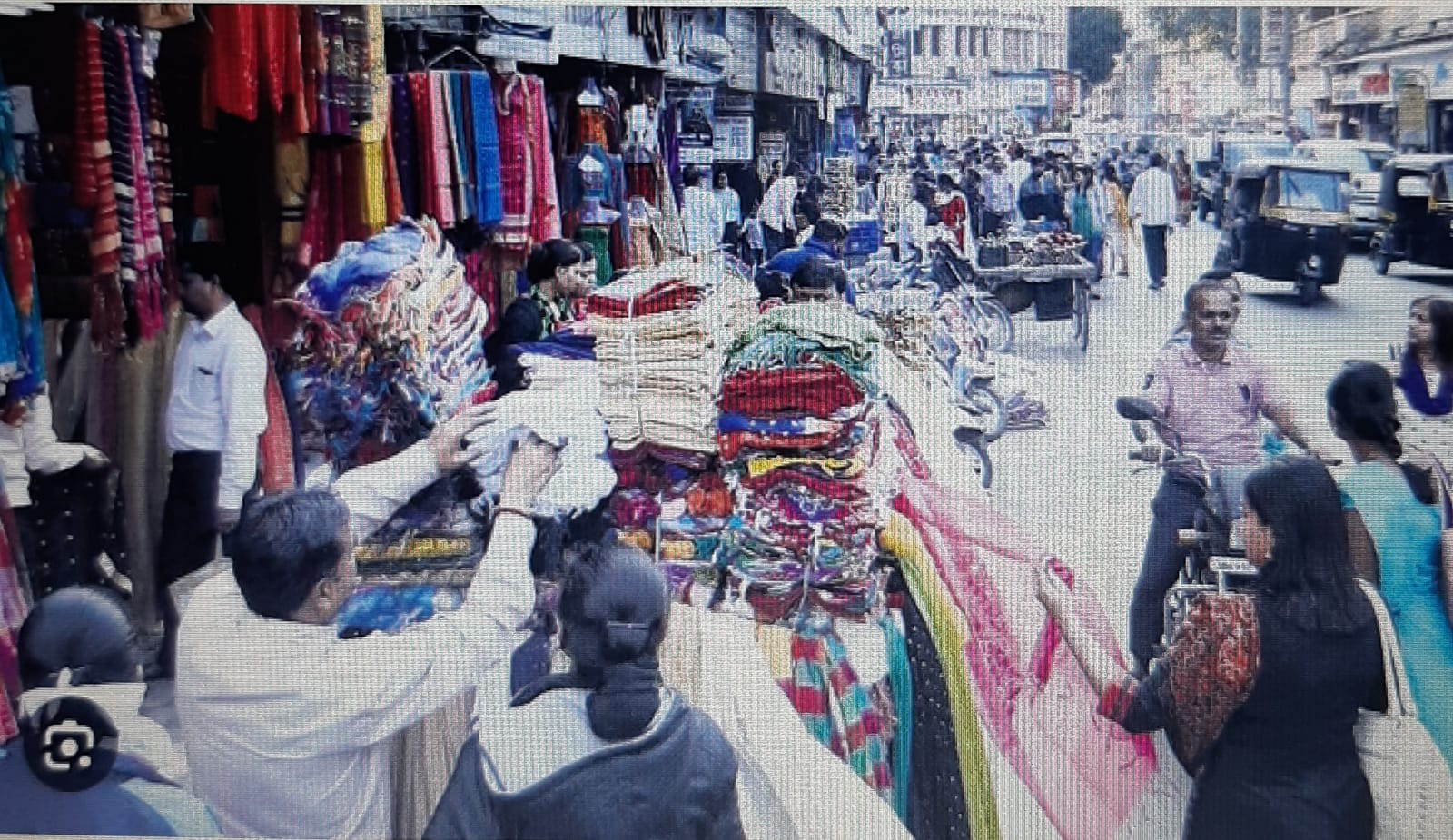

Unfortunately, in India, when footpaths exist (and there are some fine ones along many roads and streets in different towns and cities), their purpose is to serve the following:

- – free motorways for cyclists and other two-wheelers to beat the traffic snarls on the designated motor-able roads

- – extension of roadside shops for the shop-owners

- – space for hawking (undoubtedly) cheaper and useful merchandise

- – installation or erection of street furniture of doubtful utility and poorer aesthetic value

- – all other miscellaneous activities except walking.

It is difficult to see what framing guidelines would achieve unless these were limited to the reiteration of the meaning of the word “footpath” which would have to be rendered in Hindi and all the regional languages, besides English.

Caring for the disabled and the differently-abled suggests an advanced civilization with a humanitarian outlook as well as one committed to the ideals of equality of access and the right to human dignity. Many of our footpaths need to be critically re-worked to meet these lofty standards of citizens’ wellbeing. For instance, one recalls a time when footpaths in Lutyens’ Delhi were of a height easy to negotiate on foot or even if one were pushing a wheelchair. Today most of these are of extraordinary height making it difficult for even a non-differently-abled person to ascend. The purpose of a footpath or a path for walking thus stands defeated. Footpaths need to be free also of such encroachments which come in the form of uneven construction, broken tiles, man-holes and potholes. Apart from the differently-abled, senior citizens and children should also be able to use footpaths with ease.

A related cousin to the footpath is the subway or the foot overbridge. In India, we seem to have an instinctive aversion or distrust of these ‘conveniences’ meant for pedestrians. Subways are rarely clean, they are ill-lit and often unsafe. Anti-social elements, vagrants, drug addicts are persons who make subways their haunt and make them menacing for the average law-abiding citizen. Civic authorities need to pay attention to the lay-out and architecture of subways at the time of building them so that they admit maximum light and open access for security. The subway under the Garware flyover in Deccan Gymkhana in Pune is an excellent example of a fairly clean, safe and usable subway.

Foot overbridges also need to be safe and accessible and also the approach and exit to the stairs leading to the overbridge need to be clean and free of impediments. People in India however tend not to use these not because of a lack of cleanliness (which we all take for granted), but because these are either inconveniently located for walkers or because neither walker nor motorist is used to traffic discipline or road safety rules. Perhaps something akin to a social audit needs to be undertaken by the authorities to figure out how to make foot overbridges convenient of access and also a habit among the public.

Construction and inauguration of multi-crore ‘sky walks’ in different cities are now in vogue. But how many use them is rarely asked or answered. It seems the interest of local government politicians, officials and contractors is limited to awarding of contracts and ensuring payment to contractors. How else can one explain the manner in which two overbridges were constructed near Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium in Delhi in 2010 during the CWG and how, not even a hundred pedestrians use them every day. Likewise, the sky-walk constructed near Tilak bridge in New Delhi seems to be grossly under-utilised. Regular audit of use of these infrastructures by civic authorities and citizens’ groups would be desirable.

It is hardly necessary to spell out how footpaths, subways and overbridges are crucial to the road safety not just of pedestrians but also of motorists. The use of all three would ease traffic jams and reduce the vulnerability to accidents for all. The Supreme Court has rendered us citizens a signal service by focusing attention on footpaths and declaring them to be a constitutional right. The local governments, their bureaucracy, the police and traffic wardens, schools and parents, and voluntary organisations all need to get into the act to educate and inform persons of all ages about safe walking and how to achieve it. And simultaneously, the civic authorities must begin to provide these amenities and ensure their upkeep at all times. Maintenance of footpaths is as important as that of roads. They not only provide ease of walking and safe walking, they beautify the roads by making them look well laid-out, clean and non-threatening.

Implementation of the Supreme Court’s directive should not be limited to framing guidelines. Footpaths and safe, pleasant walking must become a habit among citizens. While citizen groups need to drive home their demand for the rights of walkers, local governments need to prove their worth by providing this vital infrastructure for quality living. A beginning needs to be made in the cities where city corporations are relatively flush with funds. Let them prepare and publish a Master Plan in this regard in the next three months and implement it in the next nine months. Change should be visible within a year. Or else, after another year we would still be discussing whether Guidelines have been issued or not.

Mind you, the most conspicuous sign of whether a country has become ‘developed’ or not is whether it’s streets and footpaths are safe for pedestrians or not? India has the dubious record of most unsafe roads in the world. It is high time concrete action is taken by all stakeholders – local and state government officials, engineers, police officials and citizens. Time to act is now.

(Ms. Juthika Patankar is a visiting faculty in Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics and a member of Pune International Centre. She is also a former civil servant. Views expressed are personal.)