Kuwait faces a wave of bankruptcies as the COVID-19 crisis wreaks havoc on the emirate’s economy, which is in desperate need of reform.

Al-Monitor

Kuwaiti Emir Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah died Sept. 29, leaving behind a legacy of diplomacy and positive feelings in Kuwait, the Middle East and around the world. He had a reputation for being the “wise man of the region,” and in recent years worked tirelessly to end the rift within the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). A week earlier, US President Donald Trump awarded the 91-year-old ruler one of the more rare and prestigious awards given by the White House; the last one had been granted three decades ago. The White House praised Sheikh Sabah’s “tireless mediation of disputes.”

Sabah’s death occurred as Kuwait recorded over 100,000 cases of the coronavirus and could face one of the worst economic crunches among Gulf states. Deutsche Bank has estimated Kuwait’s $140 billion economy could shrink by 7.8% this year.

The statesman’s successor, Nawaf Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, 83, was sworn in Sept. 30, while the emirate could head for one of its most significant crisis in history.

“Credible sources indicate that there will be a devaluation of the currency by up to 25%, which would have a massive impact on living conditions of Kuwaitis and residents,” Kuwait-based entrepreneur and economic analyst Geoffrey Martin told Al-Monitor.

In April, the country approved a $5.2 billion stimulus package to spur lending to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). “The banking system, however, has been very reluctant to grant loans during the COVID-19 crisis, especially since a lot of these SMEs are on the brink of bankruptcy,” Kuwait-based senior economist Chaker El Mostafa told Al-Monitor.

No plans to bail out private sector businesses or to actively support some of the 25,000 to 30,000 SMEs operating in Kuwait was announced. Martin said, “It was decided that the private sector will be left on its own completely. This is what I call triage.”

Yet Mostafa said a new law that decriminalizes bankruptcy recently approved by the Kuwait National Assembly is “very important.” “It provides protection to entrepreneurs and will become a catalyst for private entrepreneurship,” he added.

According to James Swanston, an economist with Capital Economics who specializes in the Middle East and North Africa, economic reforms are “needed more in Kuwait than elsewhere in the Gulf.” Kuwait’s business environment is ranked worst among all GCC countries on the Ease of Doing Business Index.

But Kuwait is a constitutional monarchy, and the outspoken parliament often hinders reform efforts to protect generous social benefits and public sector wages. Public sector salaries and subsidies account for 71% of spending for fiscal year 2021.

While all GCC states agreed to introduce a 5% value-added tax (VAT), Kuwait is yet to announce an official date for the VAT to be imposed. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates implemented the tax in January 2018, followed by Bahrain a year later.

“The parliament is the problem in terms of passing economic reforms. No one would vote for someone who is gonna tell them, ‘Hey, by the way, you are losing 30% of your salary,’” Martin said, noting that eight out of 10 Kuwaitis work in the public sector.

The parliament has also repeatedly blocked a crucial debt law that would allow Kuwait to tap international debt markets to fund its budget deficit. The International Monetary Fund estimates it could reach 11% of the gross domestic product this year.

“I cannot accept someone who is illiterate economically to decide my future,” Mohammad Aljouan, a Kuwaiti senior adviser in the banking sector, told Al-Monitor.

Parliamentary elections are due later this year, and Aljouan said the mandate of Kuwait’s $533 billion sovereign wealth fund should be updated to allocate part of the Future Generations Fund’s returns on investments to Kuwait’s annual budget. “Look at Norway’s wealth fund, it has a clear contribution to the budget,” he said.

Decline in global oil demand

Fifty-nine years after Kuwait gained full independence from Britain, the Gulf’s northernmost state faces the daunting challenge of steering its economy away from carbon-intensive industries. Last year, oil revenues accounted for 89% of Kuwait’s revenues.

According to studies published in September by oil and gas “supermajors” BP and Total, oil demand is expected to decline sooner than expected as the global oil market might never recover from the economic and societal impact of the coronavirus crisis.

Although GCC states have one of the world’s lowest oil production costs and might be the last oil producers standing, impacts will be felt across the board, experts anticipate.

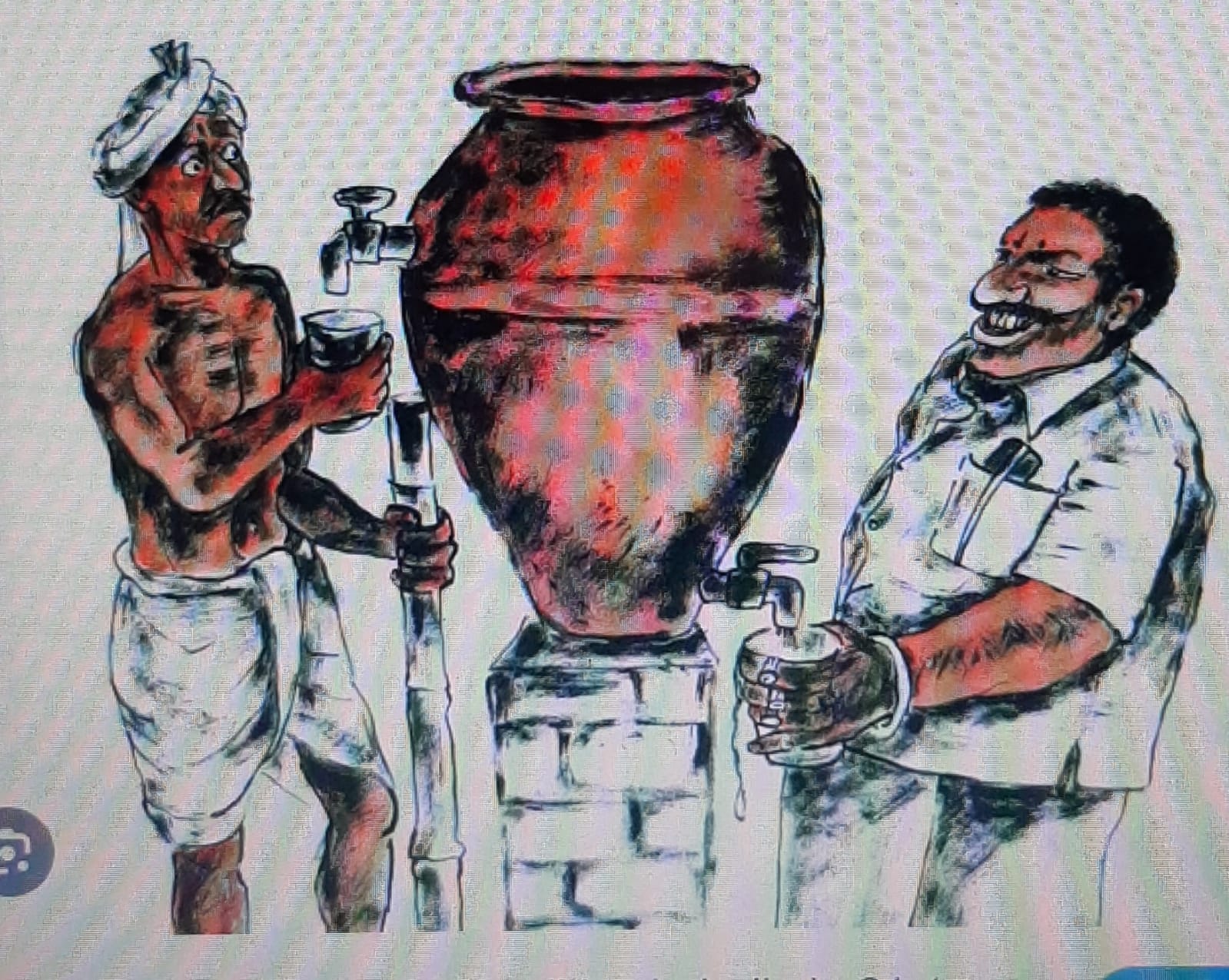

“During the pandemic, many migrant workers went unpaid or lost their jobs. All companies are in cost containment,” said Hari Krishna, a Nepali migrant worker who lives in Kuwait and is a board member of Shramik Sanjal, a network of workers from Nepal.

Like other GCC countries, Kuwait relies heavily on low-income foreign laborers who account for nearly 70% of the population — a disposable workforce entitled to no social rights and seen as the first variable for adjusting any economic contractions.

Yet Krishna believes foreign low and semi-skilled workers will remain the backbone of Gulf economies in the post-oil era. “I am hopeful there will still be many job opportunities for Nepali migrant workers in the region,” he told Al-Monitor.

(Courtesy/with thanks: Al Monitor)